In this cycle, we turn our attention to what might be called metalinguistics. We’ll explore language, letters, and numbers as a spiritual reality formed by a pattern of symbols that organize existence. This goes beyond language in the traditional sense. We’ll delve into universal symbolism, the information codes that underlie the universe’s genome. The profound language spoken by all things traces back to the sacred names handed down by the Creator to Adam.

In our first lecture, I aim to provide foundational material and an introductory overview of the topic. We have a long journey ahead, and many insights will unfold along the way. So, let’s begin with a general exploration of languages.

Currently, the world boasts between 6,000 and 7,000 languages, with the exact count depending on how dialects are classified. Among these, the majority have a small number of speakers, often limited to a single village. A dozen or so languages, including English, Chinese, Spanish, Arabic, and Russian, have millions of speakers each.

Linguists have long observed similarities among languages, leading to the categorization of related families and macrofamilies. This family tree metaphor suggests that dialects diverge from a single language over time, becoming distinct languages themselves. The more time that passes, the less obvious the connections between these languages become. It’s estimated that about a thousand years is enough for speakers to cease understanding each other in everyday conversation.

Consequently, the reconstruction of proto-languages proceeds as follows: starting with the proto-languages of closely related groups, they are compared to reveal their common ancestor, and so on, until we hypothetically reach the proto-language of humanity. This ambitious goal has yet to be achieved, and doubts linger about the feasibility of reconstructing such a proto-language, at least at the level of basic vocabulary. The deeper we delve into history, the fewer coincidences we find.

Today’s linguistic comparative studies present a complex picture. From the hypothetical proto-language of Turit, dating back about 50,000 years, the Indo-Pacific, Australian, and Borean (northern) branches diverged.

The Indo-Pacific macrofamily encompasses around 800 Papuan languages, still internally divided into sub-families. The Australian branch split into 150–200 languages around the 7th millennium BC.

However, these distant branches pale in comparison to the Borean macrofamily, which is the ancestor of all known Eurasian languages, as well as those of South and North America. This family emerged about 20–25,000 years ago. Subsequently, African languages separated from it, followed by three major macrofamilies—Afrasian, Nostratic, and Sino-Caucasian—around 12,000 years ago, whose languages dominate the planet today.

The Nostratic hypothesis, proposed at the beginning of the 20th century by Danish linguist Holger Pedersen and later developed by Soviet scholar Vladislav Illich-Svitych, suggests that about 12,000 years ago, a common Nostratic language existed, from which Semitic, Indo-European, Kartvelian, Uralic, Altaic, and some other languages later diverged.

Semitic languages include Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew; Indo-European languages encompass German, Russian, English, Greek, Latin, Farsi, and Sanskrit; Altaic languages feature Mongolian, Japanese, and Turkic; and Uralic languages are represented by Finno-Ugric languages. The largest representative of the Kartvelian family is Georgian. All these languages, according to Nostratic theory, trace back to a single proto-language that split off about 12,000 years ago.

Among these families, Indo-European languages are the most extensively studied, formerly known as “Aryan.” About 7,000 years ago, they formed a single community speaking Proto-Indo-European, which has been well reconstructed to the point that poems and fables are now written in it as an academic exercise. This community roamed the territory of modern Siberia, according to the kurgan hypothesis, before splitting into several large groups that became the ancestors of modern Germanic peoples, Slavs, ancient Greeks, ancient Romans, Persians, and Indo-European peoples of India. Some groups migrated westward, others southward, and some remained in their original areas. This is how modern Russians, Germans, Greeks, English speakers, Persians, and others came into being.

The unity of these languages is well-documented; they share common principles of word structure, grammar, and syntax, as detailed in linguistic works. Most linguistic research, about 90%, focuses on Indo-European languages, the most thoroughly studied group.

Languages evolve like ice floes breaking away from a glacier, drifting apart over time, and leaving gaps filled with water. The longer they drift, the greater the divide. The Slavic languages—Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, and Czech—diverged about a thousand years ago, retaining around 70% of their basic vocabulary and similar grammatical structures. Indo-European languages, which parted ways about 6,000 to 7,000 years ago, share about 30% of their core words. Nostratic languages, stretching back even further, have just 7-10% commonality, as seen in Russian and Turkish, Finnish, or Georgian. Comparing Russian to a Papuan language would yield almost nothing in common.

Reconstructing proto-languages involves careful methods. First, scholars focus on basic vocabulary—words for body parts, numbers, pronouns, and natural phenomena—since these are least likely to be borrowed. Borrowed words, like “computer,” introduce external influences, skewing comparisons. Instead, researchers seek regular phonetic matches. For instance, German “Zehn” (ten) and English “ten” share similar sounds, hinting at a common ancestor. Even seemingly unrelated words can share roots. English “milk” and Russian “milk” look similar but are a borrowing from Old German, while Russian “роза” (rose) and Arabic “وردة” (warda) share a deeper connection.

Everyday etymology often misses the mark. For example, “otter” doesn’t come from the Russian verb ” otodrat’ ” (to scratch). The word has ancient Indo-European roots, originating from “udra,” meaning “water.”

Take the word “wife.” It traces back to the Nostratic root “ge” (or variants like “ja” or “je”), meaning “to give birth” or “generate.” In Proto-Indo-European, “guena” referred to “woman” or “giving birth.” Over time, the Slavic languages transformed “g” into “w.” The same root appears in Old Indian “janis” (woman), Old German “quena” (woman), modern English “queen” (queen), Latin “gignere” (to give birth), Greek “genos” (origin, gender), Arabic “jens” (gender), Persian “zan” (woman), and even in “gens” (family), which gave rise to Italian and Spanish “gente” (people). This root also underlies “gentleman” and “genius,” originally the Roman spirit that accompanied a person. It might even be related to the Arabic “jinn.”

Each language interprets its roots uniquely, creating associations that lead to diverse meanings. Thus, from “wife” and “gender” to “people” and “genius,” the journey of language is one of constant transformation and adaptation.

It’s fascinating how languages intertwine history and culture. Let’s explore some intriguing examples.

The root “dr” or “dar” meant “to rotate” or “space created by rotation.” This root gave rise to Arabic “dara” (rotate) and “dar” (house). The Russian ” dver’ ” (door), English “door,” Sumerian “tur” (yard), Greek “thura” (door), ancient Indian “dvaram,” and modern Persian “divar” (wall) all share this root. It also produced the Italian “torre” and English “tower,” reflecting the concept of something tall and rotating.

The Russian word for “sea” is related to the Arabic “ma” (water). This root is found in German “Meer,” French “mer,” and Latin “mare.” Surprisingly, it’s also the origin of “marble,” derived from Greek “marmaros,” meaning “shiny,” which evokes the gleaming surface of water.

The Russian “roza” (rose) and Arabic “وردة” (warda) might seem unrelated, but they share a common etymology. The Russian word is borrowed from Latin “rosa,” which in turn comes from Greek “rhodea.” Ancient Persian had “vereda,” Aramaic “vrad,” and Arabic “warda.” This connection reveals how deeply intertwined these languages are.

Languages differ in many ways. One key distinction is in sounds. All languages use vowels and consonants, but the variety is astonishing. Some languages have up to a hundred letters, while others like Rotokas (Papua New Guinea) have only six consonants. The Taa language (Botswana) boasts 47 non-clicking and 78 clicking consonants, showcasing the incredible diversity of phonetic systems.

Vocabulary differences are even more striking. Different languages name things uniquely. For instance, a “cat” is “cat” in English, “gorbe” in Farsi, and “Katze” in German. But languages don’t just have different names; they categorize reality differently. Consider a language that lumps cats and dogs into one category. To us, this seems bizarre, but it’s a reflection of the language’s unique worldview. Russian, for example, distinguishes between “rooster” and “chicken,” recognizing them as separate animals despite their shared species.

Abstract concepts further highlight language differences. The English word “mind” has no exact equivalent in Russian, German, or French, requiring a more descriptive approach. Religious terms like “Sharia” and “wilayat” present another challenge. They embody complex concepts that defy straightforward translation.

Some languages divide body parts more precisely than others. English distinguishes between “arm” and “hand,” while Farsi uses a single word for both. Similarly, Russian distinguishes between different modes of movement (go, fly), while Farsi combines them into one verb (“raftan”).

Mastering a foreign language is about more than memorizing words and rules. It’s about adapting to a new way of perceiving the world. Once we’re comfortable with our native language’s “map of reality,” switching to another becomes challenging. True fluency requires thinking in the foreign language’s terms.

Some languages, like certain Australian Aboriginal tongues, have unique spatial orientations. Instead of left-right or front-back, they use cardinal directions. Imagine saying “an ant is crawling to my north” instead of “to my left.” Expressions like “raise your western hand” or “step south” become commonplace in these languages, reflecting their distinct worldview.

In summary, languages are windows into different ways of experiencing reality. From sound systems to vocabulary, they reveal the richness and diversity of human thought.

To speak a language effectively, one must possess an innate sense of direction. This internal compass guides us, enabling us to articulate even the simplest ideas. It turns out that some speakers of this language indeed have such a compass. Research has shown that they can sense cardinal directions, even in darkness or dense forests, with remarkable accuracy. One person, describing a shark attack, noted that the shark came from the north—an observation that might not be the first thing on one’s mind in such a dire situation.

Another striking example of how languages shape our perception of the world is their treatment of colors. In Russian, there is a distinct word for “blue,” but English lacks such a distinction, using “blue” to cover both shades. Many languages merge “blue” and “green,” considering them indistinguishable. In the ancient Indian Vedas, references to the heavens often omit any mention of color, leaving their hue undefined.

But these examples will not be the most surprising, given that the languages of some African peoples have only two colors-black and white, more precisely, “dark” and “light”.

In ancient Greek, too, there were no words for many of the colors we are used to. In Homer’s poems, black, white, and red are found. There is no blue color. Homer’s sea is purple. This at one time even gave rise to a hypothesis about the alleged color blindness of the Greeks. But in their language there were many words that express the intensity of color, that is, the degree of radiance and brilliance.

In some languages, the sky is called “black”. For us, it is so natural that the sky is blue or at least blue, it is so wild to call it “black” that it really suggests itself the version with colorblindness of those peoples whose languages are arranged in this way. However, special studies were conducted that found out that visually they distinguish colors in the same way as we do.

Why do they have no words for these flowers, why is their language so stingy with them? Obviously, because they think it’s unimportant. Highlighting a rich palette of colors was irrelevant to their society — just as it is not necessary for each of us, for example, to highlight hundreds of colors until he is engaged in car sales, and then he will simply need words to highlight the shades of their colors.

For the peoples living in the south, there is no need to distinguish between types of snow, since there is little of it in their region — and therefore in their languages there will be one word “snow”. But for northern peoples, who often deal with snow, it is important to distinguish its shades — and therefore their languages have developed a rich system of corresponding concepts — for example, in Russian “blizzard”, “blizzard”, “snowfall”, “snowfall”, “powder”, “pad”, etc. etc. All these words express the same phenomenon, snow, but from a special point of view.

Many languages that emphasize kinship relationships have a rich vocabulary to distinguish distant degrees of relation. Russian once had such terms, but today they are largely obsolete as social structures have shifted, with most families now consisting of just parents and children. Words like “sister-in-law” (husband’s sister), “brother-in-law” (husband’s brother), and “brother-in-law” (wife’s brother) are on the brink of disappearing. Terms like “stryi” (father’s uncle), “shurich” (son of a brother-in-law), and “yatrovka” (wife of a brother-in-law or brother-in-law) have vanished entirely.

In numerous languages, there is no single word for “brother”; instead, there are distinct terms for an older brother and a younger brother. Some languages even differentiate “father” depending on whose father is being referred to — the father of a son versus the father of a daughter. For example, when speaking these languages, one cannot simply say “father”; one must specify whose father is being discussed.

Another fascinating aspect of how languages shape our worldview is their treatment of gender. Some languages, like Farsi, Chinese, Turkish, and Finnish, do not have gender distinctions. In English, gender is applied only to humans and sometimes animals, using “he” or “she.” In Tamil, the masculine gender is reserved for males, the feminine for females, and the neuter for inanimate objects. However, many languages arbitrarily assign genders to objects without any clear logic. Russian, German, French, Greek, and Spanish fall into this category. Why is a chair “he,” the sky “it,” and a star “she”? In German, the neuter gender can even be used for women, treating them as “it”: “das Mädchen” (girl), “das Weib” (woman), “das Fräulein” (unmarried girl).

The gender system strongly influences the associative range of native speakers. Russians may wonder why the Germans portray sin as a woman. The fact is that die Sinne (sin) is feminine in German. Death in Russian culture is understood as an old woman with a scythe, and in German-as an old man, because the word der Tod — death )is masculine.

This is something that concerned vocabulary. The third level where language differences exist is grammar. The grammatical structure of a language is the obligatory forms that words in a given language take if we want to connect them with each other and thereby say some meaningful phrase. The language seems to see the world through colored glasses, through such categories that it obliges each of its native speakers to apply. For example, in Russian there is a category of numbers — singular and plural. You can’t use a noun without putting it in one of these forms, except for some exception words, such as coat, which don’t have a plural form.

Or take the same category of genus. In Russian, the noun must be either feminine, masculine,or neuter. Accordingly, and the verb that agrees with this noun. We say “the month has risen”, but we can’t say “the month has risen”. But even if we say “the moon has risen”, it will still be a category of gender, only incorrectly applied. This is how the Russian language sees the world-through the category of gender. You can’t speak Russian without using this category.There are no neutral words.

But, as we have already said, there are quite a few languages that do not have this category at all. You can read a long text in such a language and not understand whether it is a man or a woman. In the picture of the world of these languages, gender is not fundamental, it does not play a role. It can, of course, be expressed if desired, but not by grammatical, but by descriptive means, that is, by explicitly stating that such and such a person is a man or a woman.

The human imagination in inventing grammatical forms seems boundless. In Native American languages like Aymara, there’s an evidential category that demands you specify how you know something each time you speak. For example, saying “Something happened yesterday” is straightforward in Russian, where the verb’s tense indicates the past. But in Aymara, you must add a special grammatical marker to show exactly how you know it—whether you saw it, assumed it, or heard about it. This is a grammatical requirement, integral to the language’s structure. Aymara speakers can’t simply say, “In 1492, Columbus sailed to America”; they must express it as “Rumor has it…” or “I was told that Columbus sailed to America in 1492.”

Why? Because for these languages, categories like “known” and “unknown” are crucial. They divide reality differently. In Aymara, the past is seen as what lies ahead, and the future as what’s behind us. The expression nayra mara, meaning “last year,” literally translates to “the year ahead.” This unusual perspective stems from the idea that the past is known and clear, hence it “lies before us.” The future, being unknown and incomprehensible, is “behind us,” in an uncharted area.

On the other end of the spectrum, isolating languages like Chinese, Vietnamese, and Thai are quite peculiar. They have few grammatical categories—no tense, case, number, or gender. Words in these languages remain unchanged, like individual blocks or atoms, with boundaries matching their roots. Meaning is determined by word order in the sentence. For instance, the Chinese word hao serves as a noun in siyu hao (“to do good”), an adjective in hao ren (“good man”), and a verb in ren hao wo (“man loves me”).

The picture of the world in such a language will be inaccurate and blurry. Hence the name that linguists used to call them – “amorphous”. After reading the classical Chinese text, you may not understand when it happened-in the present tense, in the past or in the future, who is the person of the action-a man or a woman. You may or may not be able to guess this from the context. That is, it is such an amorphous drawing, visible as if through a haze, similar to a Chinese painting. If you look from the Chinese point of view at our languages, which are full of grammatical forms, they may seem to him like a kind of prison, putting speech behind the bars of numerous rules.

Today, English is approaching the Chinese model, because it is also on the way to becoming an isolating language, losing grammatical categories. Russian is still far from this; it has preserved to the greatest extent the complex grammatical structure characteristic of the Indo-European proto-language. But it is also simplified, and some grammatical categories are eliminated. Let’s take Pushkin’s lines:

Sing, lovely one, I beg, no more

The songs of Georgia in my presence,

For of a distant life and shore

Theyir mournful sound calls up remembrance

What is “theyir” in Russian language’s context? This is a feminine plural form that has disappeared from the Russian language, leaving only “they” — for both women and men. And in the time of Pushkin, this form existed and was used. Until recently, the Russian language had the seventh case, which also disappeared, once there was a dual number, which, like in Arabic, was formed using the suffix “a”. It is still preserved in such words as eyes, sides, horns, banks. This is exactly the dual form, because in the plural we would have to say eyes, sides, horns, take care.

In general, linguistics has a sinusoid theory, according to which languages move from complexity to simplification, and then again from simplification to complexity. For example, Farsi, which in ancient times was a morphologically very complex language, then greatly simplified according to the” English ” model, and today, apparently, is increasing a new complexity.

So, a language contains a certain code, a certain grid, which it forcibly imposes on the speech of anyone who speaks it. In each given language, you can express your thoughts only in one way, and not in another, only from a certain angle.

As we have already mentioned, the difficulty in mastering other languages is precisely due to the fact that we are used to the worldview of our native language, to how it divides reality. If there are some grammatical categories in the language being studied that are not present in our native language, then they will seem redundant and superfluous to us, whereas for native speakers of that language they are completely natural. Since school, we all remember what a nightmare the temporal system of English verbs seemed to us: we did not understand why it was necessary at all, why all these terrible “completed in the past” and “long in the present”, because in Russian with its simple temporal system this is not the case.

On the other hand, learning a language without gender categories can leave us feeling as if we’re missing something essential. An English speaker who learns Russian might long for the familiar system of tenses, particularly the nuanced “plusquamperfect.”

But what truly sets languages apart? Are these differences profound and irreversible? Can one language truly lack the ability to express what another can? In practice, this is far from the case. You can convey any idea in any language. Even languages without specific words for colors like blue or red can describe them. For instance, you could say, “This object is the color of raspberries.” Furthermore, languages can quickly adopt new concepts, such as modern math or programming terms.

The essence of language lies not in what can’t be said, but in what must be addressed. Speaking Russian demands attention to gender, a requirement that isn’t present in Chinese or Farsi. While these languages can express gender through context or description, Russian speakers have no choice but to adhere to grammatical gender rules. In Farsi, saying “bo dust budam” — “I was with a friend” — doesn’t specify the friend’s gender. “Dust” can refer to a friend of any gender. You can clarify if you wish, but the language itself doesn’t enforce it. In contrast, in Russian, the phrase “Я был с другом” (I was with a friend) clearly indicates the friend is male, unless you specify otherwise.

Farsi and English, unlike Russian, have a sophisticated tense system that intricately captures the duration of actions. In these languages, speakers must pay attention to temporal nuances, whereas Russian allows for more flexibility in discussing actions without emphasizing their duration.

Languages differ not by what they enable one to express, but by what they inevitably highlight. Each language compels its speakers to focus on specific aspects of reality, reflecting its unique structure.

Learning a foreign language is akin to adopting a new way of perceiving the world. Shifting to a different language is akin to transitioning to a different coordinate system. As Goethe aptly noted, a person who doesn’t know foreign languages doesn’t truly grasp their native tongue, as they lack a comparative perspective.

There’s a paradoxical interplay between the differences and similarities of languages. Each language offers a distinct worldview, guiding speakers’ thoughts in particular directions. Yet, all languages share fundamental elements—vowels, consonants, syllables, words, sentences, subjects, and predicates. No language contains an entirely unique concept, sound, or form that cannot be conveyed in another. Every language can be learned by speakers of other tongues, suggesting they are all variations of the same archetypical form. Deep down, they are essentially identical.

There exists a shared, a priori language of the Spirit that we all possess, manifesting through every spoken and written tongue. This is why translation is possible. In their work, translators grapple with this linguistic paradox daily. They recognize that languages are fundamentally distinct yet manage to bridge these gaps continually.

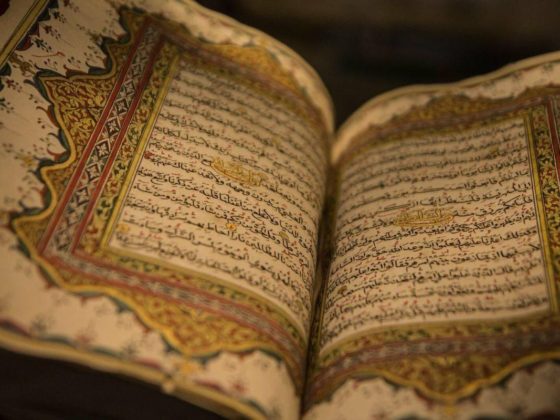

Viewed from this perspective, languages aren’t separate entities but rather different facets of a single, overarching human language. They are, in essence, the various colors and shapes of a single diamond. The Qur’an beautifully captures this idea: “Among Its signs is the creation of the heavens and the earth, and the difference of your languages and colors” (30:22).