To understand the mechanism of human thought, we must first explore the structure of reality and humanity’s place within it. The human being is composed of three primary levels: body, soul, and spirit (with a fourth, less discussed aspect).

In the macrocosm, these correspond to Universal Nature, the World Soul, and the World Spirit. Humans embody the essence of the macrocosm; as Imam ʿAli (A) said, “You think you are a small body, but within you lies a great world.“

I have explored these levels in detail in the series “Man in Islam.” Here, I will briefly summarize them. The series “Language, Letters, Names” builds on these themes, so familiarity with “Man in Islam” is recommended. Some concepts will be revisited, while others will be assumed to be understood. If anything remains unclear, refer back to “Man in Islam.”

The World Soul is known as the Preserved Tablet (laūḥ al-maḥfūẓ), the Green Light, and the lower right pillar of the Throne. It is the repository of all creation’s images, the universal nafs, and the hidden Fire beyond the tangible world. It is an informational field containing the blueprint for all things. Modern science is inching toward this concept, asserting that the physical world is fundamentally information-based.

The World Spirit, the Holy Spirit (rūḥ al-qudūs), is the White Light, the upper right pillar of the Throne. It is the Pen in Sūrat al-Qalam, recording the past, present, and future. It is the “Lamp” in Sūrat al-Nūr, the highest creation in limited being, the First Intellect (ʿaql), and the source of all ideas. The Spirit contains the luminous essence of every being, its intelligent blueprint, according to which all existence is formed.

The human being mirrors these cosmic levels. Our physical body corresponds to Universal Matter. Our nafs, or individual soul, corresponds to the World Soul, encompassing the informational programs that govern our actions. The vegetal soul sustains our body, the animal soul enables movement, and the rational soul connects us to the spirit and enables thought.

The World Spirit is manifested within each of us through the breath of the Most High:

“And He breathed into him of My Spirit” (38:72).

The phrase “of My Spirit” indicates a cosmic connection, as the Spirit is singular and immaculate. It is not a substance within us but a beam extending from the universal Intellect, connecting us to the divine source.

The Almighty says to the angels,

“When I have fashioned him proportionately and breathed into him of My Spirit, then fall down prostrate before him” (38:72).

This act elevates humans above angels, who are manifestations of the Spirit.

The angels, created from the Intellect’s radiance, serve as messengers of divine grace (faḍl). They are intermediaries between the universal mashīyah (Divine Will) and creation. The angels prostrate before humans because they are entrusted with the names—the words—of existence: “And He taught Adam the names—all of them” (2:31).

Through the Spirit, humans gain access to the essence of all things. The rational soul, called nafs nāṭiqah qudsiyyah, reads from the universal Intellect, perceiving the essence of each thing. This process, known as ideation, is the foundation of abstract thought and language.

Unlike animals, humans think abstract ideas detached from physical reality. These ideas are expressed through language, which refers to concepts rather than specific objects. When we say “tree,” we mean the idea of a tree, not a particular one in the forest. Language allows us to communicate beyond immediate experience, a unique human capacity.

Animals communicate through signals, often mistakenly called a “language,” but this system bears no resemblance to human language. A bee, for example, uses intricate flight patterns to inform its fellow bees about the location of honey and the distance to it. This discovery led to the misconception that animal communication is akin to human language, merely an evolutionary precursor. However, there is a fundamental difference: human language is not just a means of transmitting messages; it is an instrument of thought, enabling us to manipulate abstract ideas detached from their physical manifestations.

A bee might gather nectar from flowers its entire life, but it never forms the concept of “plant” in its mind. Animal thinking is confined to immediate, practical situations, lacking an inner world of abstract concepts. They see and hear, but do not comprehend what they perceive. Human language points to meanings, while animal signals always refer to concrete objects or events.

For instance, a bee’s dance communicates its exhaustion from a long flight, not an abstract idea of distance. Similarly, a macaque’s alarm call serves to alert others to immediate danger, not to convey a broader concept. Animal signaling systems are genetically determined and limited to specific situations. By contrast, human language can express an infinite range of meanings, including those unrelated to practical needs.

Efforts to teach apes human language have failed. While apes can learn a rudimentary signaling system using signs, such as the sign language taught to deaf and mute chimps, they do not truly understand language. A chimp might sign “Give sweet” when pointing at a banana, but this is not the formation of language. Rather, it is the application of associative memory and practical intelligence. The word is a stimulus, not a symbol pointing to a meaning. For the chimp, words remain external stimuli, devoid of inner significance.

Specific speech disorders illustrate the profound difference between humans and animals. In amnesic aphasia, patients cannot recall words, either entirely or for specific categories like colors. Experiments with such patients reveal their inability to abstract concepts. A patient might visually distinguish red from other colors but cannot name it. Without the abstract concept of “red,” they cannot recognize all red objects as belonging to the same class. An ordinary person, however, labels objects as “reds,” enabling them to quickly identify other red items. The aphasia patient, lacking this abstract concept, is left helpless, unable to distinguish colors without a visual reference.

The difference between humans and animals lies in their capacity for abstract thought and language. Animals perceive the world through concrete, immediate sensations—a tree is always “this tree,” a house is always “this house.” They cannot conceive of general concepts like “tree” or “house.” In contrast, humans use language to create abstract ideas, allowing us to think about concepts detached from specific instances.

Consider an experiment where a patient, having lost their ability to name things, could only see individual objects. They could not recognize the abstract concept of “red” but had to compare specific red objects to find similarities. This example highlights the power of language. It enables us to hold an abstract picture of reality in our minds, unbound by immediate experience.

Animals, on the other hand, are limited by their immediate environment. They lack the ability to think beyond concrete situations, which is why they cannot suffer from conditions like schizophrenia. Humans, with their capacity for abstract thinking and language, are “above” the world, capable of reflecting on themselves and their experiences. This elevated perspective is both a blessing and a curse, as it allows us to be self-aware but also prone to mental illness.

In patients with aphasia, the loss of words is linked to the forgetting of the concepts they represent. These individuals lose not just the word “red” but the entire concept of “red.” It’s as if their “speaking soul” cannot access the universal ideas stored in their consciousness, much like a biological error prevents an organism from reading certain genetic information.

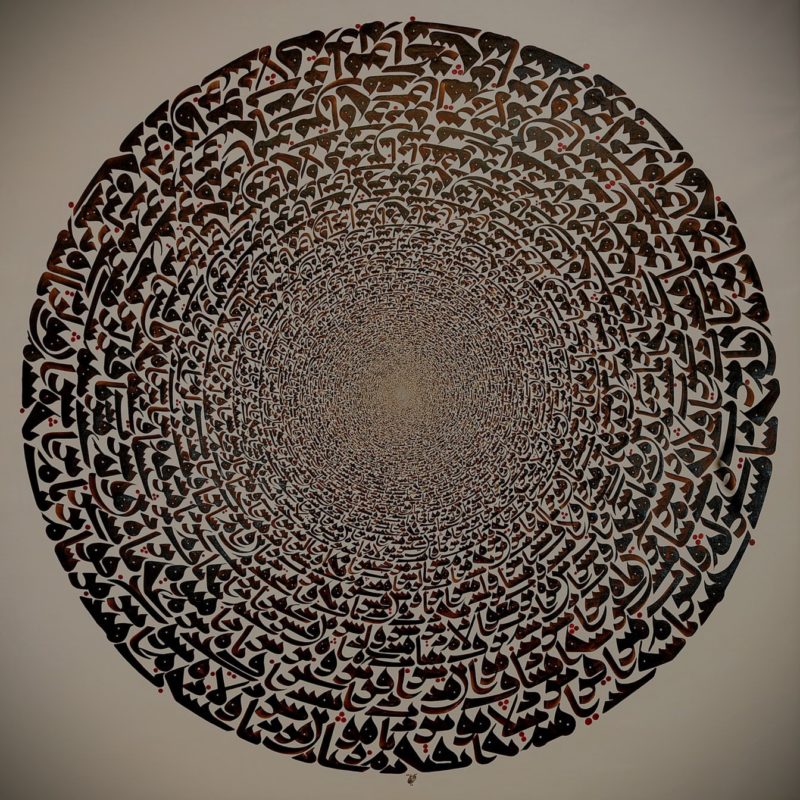

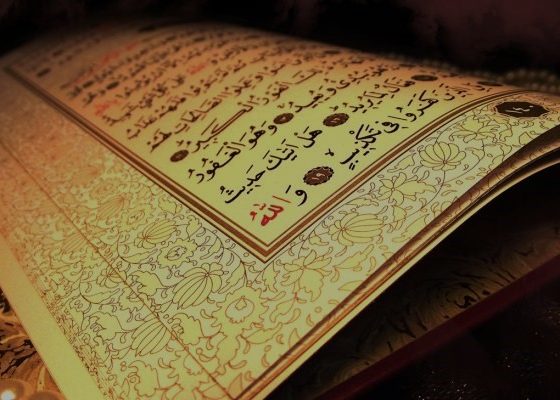

Words and ideas intertwine into a seamless whole. This is beautifully captured by the Arabic word “ism,” which simultaneously means both “name” and “idea” of an object. According to the Qur’an, Allah taught Adam all these names, signifying concepts rather than mere words (2:31). Allah imparted to Adam not just words but concepts, as there are multiple words for one concept in different languages, but the essence remains singular. Through this teaching, Adam became a fully human being, not just a potential one, a “model of a man.”

Thus, there’s no such thing as thinking without language. We might attempt to think without words, using images, but this is fleeting—thoughts quickly vanish. Even this kind of thinking is rooted in linguistic understanding. Concepts don’t emerge in our minds before we assign them words; they develop alongside language learning. If a child isn’t taught language, they won’t form concepts or abstract categories. By naming objects, we guide the child’s consciousness to categorize them. For instance, calling various round objects “balls” helps the child understand they belong to the same category.

A child’s ability to recognize concepts is innate, but it must be nurtured. For example, a child might initially call everything a “ball,” including cups and vases. Correcting them helps form new concepts, gradually creating a network of words and categories to perceive the world.

This is also evident in deaf-blind children. They rely solely on touch to understand the world. Without language, they’d exist on the fringe of humanity, barely meeting basic needs. However, teaching them language through touch allows them to become fully functioning members of society.

Language is what truly humanizes us. It’s not just speech but thought, actions, and the entire fabric of human existence. Without language, we’d be lost, lacking the tools and instincts animals possess. Language is our greatest asset, setting us apart from other species. Without it, we’d perish within a century.

A surprising conclusion emerges: what has no name doesn’t exist. To us, a “tree” is a tangible object, but to an animal, it’s a collection of sensory impressions—something tall, green, and “climbable”. Concepts like “tree,” “flower,” and “river” are human abstractions. We learn these concepts through language, and it’s essential that someone teaches us—whether it’s English, Russian, Japanese, or Arabic. This chain of learning leads back to the origin of language, suggesting it was given by The Creator.

Language doesn’t just reflect the world; it shapes it. It’s not that things exist independently and language merely labels them. Language molds our perception of reality. This is the opposite of how we naturally think. The world is a reflection of language, which itself reflects ideal prototypes in the World Spirit.

Let us return to the tree. There exists a vast array of trees in this world, each differing not only in species—firs and oaks, birches and lindens—but also in individual characteristics. This multitude is a manifestation, drawn from the archetypal idea of “tree”—an informational super-form that exists in the imagined World Soul and as a pure idea in the World Spirit or Intellect.

When we conceive of a tree, our rational soul turns to the Universal Spirit to access this archetypal idea. Upon reading it, our rational soul expresses it through language, assigning it the vocal code “tree.” Importantly, this word denotes the idea, not the physical object. By saying “tree,” we are referring to the concept of “tree,” applicable to all individual trees, not a particular one. This idea lacks physical attributes like color, weight, size, or composition; it is purely abstract. Language operates with such abstract entities, a fundamental distinction from animal communication, which relies on gestures and sounds to indicate specific objects.

Language also encompasses concepts without sensory counterparts in the external world, such as “love,” “truth,” “beauty,” “the One and the Many,” “the Whole,” and “the Part.” For example, who has ever seen “love” or touched “beauty”? Where in the external world can one find “the Whole” or “the Part”? Understanding these concepts requires prior knowledge of “Whole” and “Part,” which do not exist in physical reality.

Numbers are another example of pure, ideal entities. In nature, there is nothing inherently “two” or “three.” We impose numerical order by grouping objects and labeling them as “two” or “three.” These numbers exist as abstract categories, independent of specific objects, allowing us to perform mental operations that form the foundation of mathematics. Through these operations, we establish abstract, a priori laws, such as “two twice three is six,” which apply universally to objects and situations, regardless of their physical properties.

Language, then, is the expression of abstract ideas and values, a projection of the World Spirit onto the human plane. It is the stabilized totality of names, resulting from countless spiritual acts performed by millions of people over time. The names of all things, their ideal prototypes hidden within the World Spirit, are apprehended by humans because a spark of that Spirit was breathed into us. “And He taught Adam all the names” signifies that He revealed the essence of all things to him. With these names, humanity holds a unique position, commanding the angels to prostrate before us.

At its core, humanity extends into the hidden strata of reality, transcending sensory perceptions to grasp eternal, ideal entities. This ability to distinguish essence from existence is uniquely human, allowing us to understand the objective order of ideas and values.